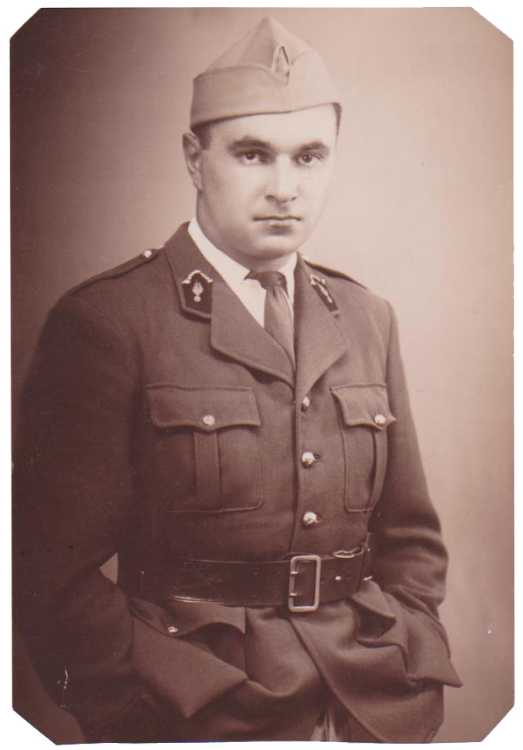

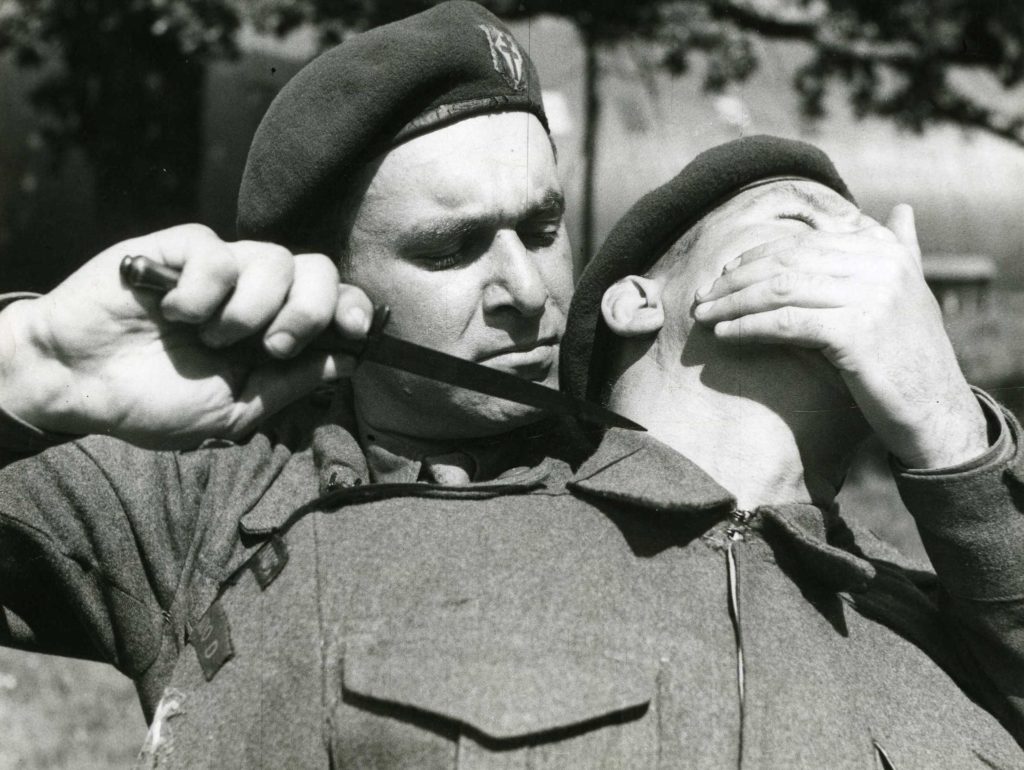

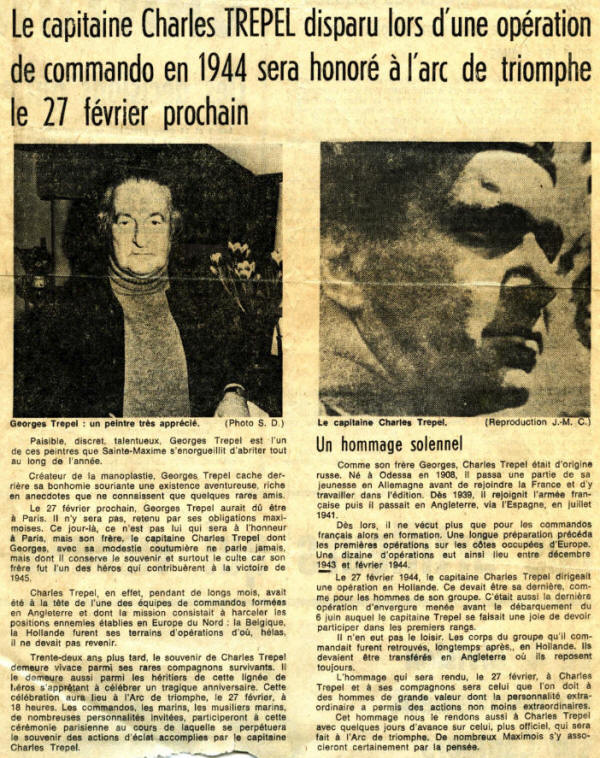

Charles Trépel was a great soldier, one of the best. He lived a life too short, that didn’t allow him to reach his full potential. Nonetheless, he did live a very intense life. Born on September 21st, 1908 in Odessa, Crimea, Russia, he allegedly descended from a Czechoslovakian origin. He spent his youth in a very chaotic socio-political context. Following 1917’s Russian revolution, he left for Germany, where the baseness of his life makes him go from extreme misery to opulence and back again. The rise of Nazism, starting from 1933, was a foundational element of his lifeline: it represented a mortal foe for him. The same year, he left Germany for France and relocated in Paris. At that time, he already had an exceptional physical shape, and was especially fond of athletics. Shortly after he was mobilized in the French army’s artillery, he was made lieutenant in june 1940, before being demobilized a few months later. He then left for Spain, to join Barcelona, then Gibraltar, in September 1941. He established himself in the FFL Camp of Old Dean, in England, in November 1941. There, he started following a special training. He was assigned to the FNFL in may 1942, under Philippe Kieffer’s command, in the british Special Service Brigade. Their unit, the 10 Commando Inter-ally, stayed in Wales until may 1943. Trépel couldn’t participate in the Dieppes Raid of August 28 1942 because he was only a lieutenant. But he made the most of this setback, and took the time to study the combat and landing techniques of the british army. 1943 was a major year in Trépel’s life: he earned commandment of the new Troop 8, and started selecting his men according to a draconian process involving walking 7 miles in 60min. The selection took place in Achnacarry, Scotland. The difficulty of the selection was justified by Trépel’s standards, but also the rumor of Europe’s imminent liberation, that was fuelled by the recent successes in North Africa. Trépel wanted to be ready for action. However, this selection wasn’t devoid of humanity: Trépel treated his men with the utmost respect, and oftentimes he would personally monitor the healing of his men’s wounds. He was tough, but he was fair, as long as his men showed their willpower. Following this commando session, 65 men received their badge and their famous green beret, thus forming Troop 8. When Trépel went back to England, he was made captain, and was thus on equal measures with the other troop leaders. The internal structure of the unit was completed shortly after, leaving Trépel free of setting up his strategy, based on individual infiltration, the real commando tactic. He was tireless, working over and over on military books, cartographies and topographies. He also worked, though in a less formal manner, on estimating the advantages and characteristics of each of his men, because of their diversified origins. It didn’t matter to him where the men came from, what mattered was what set them apart from the others, and what they could bring to the table. After the announcement of the dislocation of the Troop 10, the 8 received orders: they had to go to departing bases on the south coast of England, in order to participate in the 10 Hardtack Operations, assigned to the two French troops. Trépel was named leader of a raid on Berck Plage. His men had yet another opportunity to witness his extreme thoroughness, his attention to detail that sometimes bordered on absurdity, and his inhuman sense of anticipation. For this operation, he had handpicked his men, including some natives of the city. The raids were slated for the night of the 24th to the 25th December, however various mishaps only allowed 5 raids to effectively take place. Trépel’s raid was one of the cancelled ones, which was a huge shock for him. Following this disappointment, he went to London, and came back with a newly assigned mission and a newfound motivation. The 8 was split in 2 groups: Trépel’s and Lieutenant Chausse’s, his right hand man. Trépel’s group left for the Great Yarmouth base, while Chausse’s launched his operation on the Belgian coasts in the night of the 20th to the 21st February 1944. When Chausse came back to base, he was made aware of a disturbing rumor whereby Trépel was missing and his operation had failed. A month later, the Troop 8 finally reunited, and Bougrain, Trépel’s group’s radio operator, was able to tell the story. Their raid was directed on a point of the Netherlands’ coast, north of Schevenonger. The first assault was a critical failure. A few days later, during the second assault, and despite a lack of discretion, Trépel and 6 men boarded their Dinghy and disappeared in the darkness of the night. The Doris that had transported the men waited until 4am, and when the crew finally welcomed the Dinghy back, there were only 2 survivors onboard, and Trépel was not one of them. Despite this terrible loss, the Troop 8 participated in the D-Day, with Lord Lovat’s unit. After the liberation of Holland, the investigation launched to find out why and how the men had disappeared bore no fruits, until june 1945, where 6 bodies were found, close to their point of landing. Captain Trépel is now resting with his comrades in the british cemetery of Wistdvin, near La Haye. The cause of their death remains unclear to this day. However, the reasons why Captain Charles Trépel had made history were obvious.