Why did the United States enter World War I so late? Two and a half years after the beginning of the war, just 106 years ago, on April 6, 1917, the U.S. Congress declared war on the German Empire. The country’s multi-ethnic population included many citizens from the belligerent countries, and had expressed at the beginning of the war its wish to remain neutral with respect to the events taking place across the Atlantic. Neutrality and isolationism were still the watchwords of American foreign policy in 1914, but this must be qualified since the country became the main trading partner of the Entente at the beginning of the conflict, which without its agricultural and industrial resources would not have been able to pursue its war effort.

Despite the submarine warfare led by the Germans, as well as the torpedoing of the RMS Lusitania, a British transatlantic liner carrying, among others, 125 Americans, in 1915, which caused a strong stir among Americans, the country remained neutral. President Woodrow Wilson had in fact obtained, via protest notes, the cessation of German submarine warfare shortly after the events.

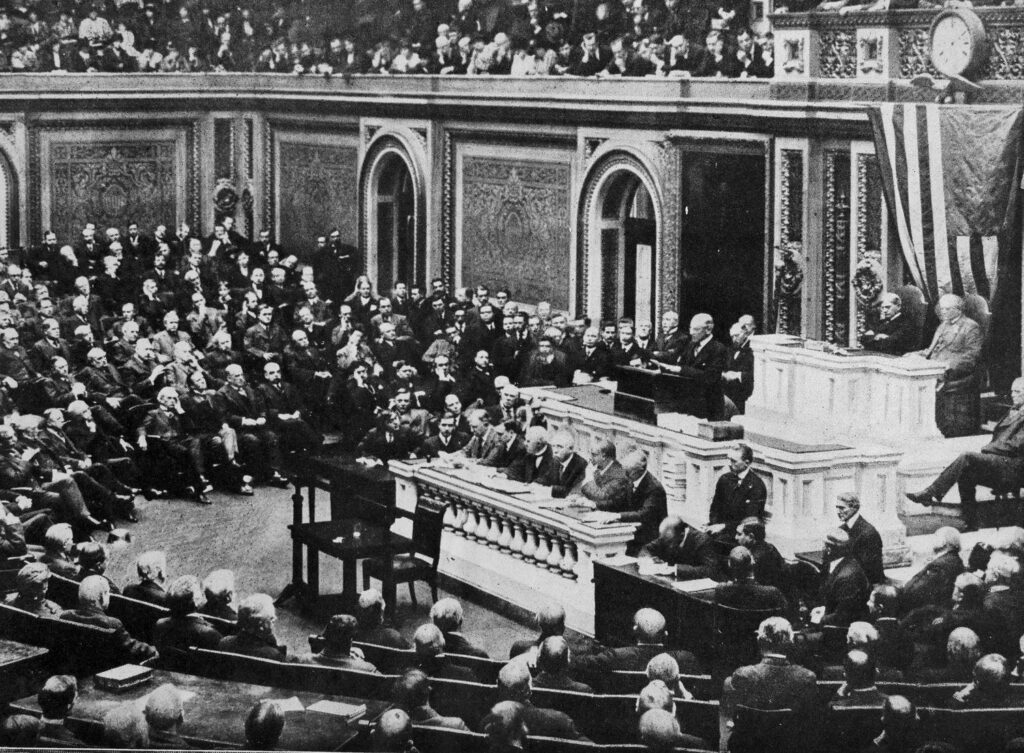

But several decisive events were to occur at the beginning of 1917, which would precipitate the involvement of the United States. Firstly, at home, the country’s neutrality had ceased to be an electoral issue after Wilson’s re-election as president in 1916. Then, externally, on the one hand, the interception by the British in January 1917 of the Zimmerman Telegram, a coded communication between the German foreign minister and the German ambassador to Mexico, in which the former ordered the latter to propose an alliance with Mexico, against the United States, a communication that the British transmitted to the United States; on the other hand, the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare by the Germans from February 1, 1917, who intended to break the supply chain between the United Kingdom and, in particular, the United States, and who began at the beginning of 1917 to sink American merchant ships in the North Atlantic, thus threatening the commercial ties between the United States and the Triple Entente. All of this prompted Wilson to ask Congress to declare war on the German Empire, a “war to end the war,” presenting it as a crusade to defend democracy against the despotic regimes of Central Europe. The request received a very positive response. This entry into the war would change the course of history and would completely reorganize the role of the country in world geopolitics. It is following this date of April 6, 1917 that the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) was sent to Europe.

We could say a thousand and one things about this entry into the war, and the rest of these events, but Dominique François will speak better than we can. On April 28, at 8 p.m., at the museum, the historian and author will discuss the role of this Expeditionary Force in the conflict, for a conference that promises to be fascinating!

Reservations:

- infos@airborne-museum-org

- 02 33 41 41 35